Giving Effective Feedback

October 2, 2015 Leave a comment

This is part 3 of my Feedback series —

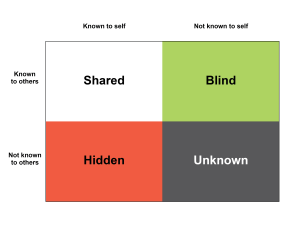

While soliciting regular feedback (series part 1) and making our hidden selves known (series part 2) are foundational to awareness, we can also contribute to a more open, trusting environment if we learn how to deliver feedback. This final post in the series offers tips and techniques.

Concepts of Giving Good Feedback

- Give feedback ONLY to be constructive and helpful – otherwise it becomes a weapon and can tear people down. Check your motives carefully.

- Describe only observable behaviors – don’t judge it as good or bad, or infer the person’s motive.

- Evaluate the behavior not the person.

- Provide a balance of positive and negative feedback, otherwise people might become demoralized, or not get the message.

- Beware of feedback dumping. Select two or three important points you want to make and offer feedback about those points.

Steps to Giving Constructive Feedback

Whether you are initiating feedback, or the other person has requested it …

- Briefly tell the person what you’d like to cover and why you think it’s important. Then ask if this is a good time to discuss, and if not, when they would like to do so.

- “I have a concern about.” “I feel I need to let you know.” “I want to discuss.” “I have some thoughts about.” Then…

- “May I offer that to you?” “When is a good time?”

2. Describe specifically what you have observed, and the reactions of yourself and others.

- Have a certain event or action in mind and be able to say when and where it happened, who was involved, and what the results were.

- Begin with something positive – or something that shows empathy.

- “I know you are passionate about this topic and that’s great – exactly why we hired you.”

- Stick to what you personally observed and don’t try to speak for others. Avoid talking vaguely about what the person “always” or “usually” does.

- “Yesterday afternoon, when you were speaking with the client, I noticed that you kept raising your voice.”

- Give examples of how you and others are affected. When you describe your reactions or the consequences of the observed behaviors, the other person can better appreciate the impact their actions are having on others and on the organization or team as a whole.

- “The client kept backing away from you, and I saw others in the room shrinking away from the conversation.” That conversational style doesn’t really fit this client’s personality or corporate culture. I’m worried about a potentially negative impact.”

3. Give the other person an opportunity to respond.

- Pause, then ask an open ended question that allows the person to give their perspective and their reaction.

- “I’d like to hear your perspective. What do you think?”

4. Ask permission, then offer specific suggestions that can help the person do better next time. If they would like, give practical, feasible tips.

- “Might I offer some tips?” “Would you like some ideas of how to do this differently next time?” “Next time, you might speak more slowly, pause, read the room to be sure you still have your audience with you.”

5. Summarize and express your support

- Emphasize your main points (the things you want the person to improve or know), and reinforce your faith in them.

- “The tone you used with the client in this meeting wasn’t effective, so next time, use a different approach. I will try to coach you through that if you like, and I know your intent is good. That means a lot, too.”

- “ I’m confident this will get better quickly. Thank you for being open to this feedback. ”